Since the attacks of September 11, 2001, the label “terrorist” has been used in almost every conflict to discredit an opponent. From the Chinese government accusing Hong Kong protestors of “showing signs of terrorism” to the Iranian parliament designating all U.S. forces as terrorists in the aftermath of the killing of Qasem Soleimani, it is clear that the definition of terrorism has been adapted to fit specific situations. But how did our perception of what does and does not constitute terrorism become so blurred and what are these designations based on?

It all started in the aftermath of the September 11 attacks of 2001, when U.S. President George W. Bush linked international terrorism with states such as Iran, Iraq and North Korea through the so-called “Axis of Evil.” His State of the Union Address in January 2002 set the stage for U.S. action against these states. Based on the spike in Bush’s approval ratings following the U.S. invasion of Iraq, his rhetoric was politically effective, despite the fact that the invasion and the broader “war on terror” were unrelated. The enactment of the Patriot Act in October 2001 further illustrated how invoking the term “terrorism” provides political sway, despite the law having been widely criticised for infringing upon human rights. While 9/11 necessitated a decisive response, U.S. reactions prompted not only a futile war and granted sweeping competencies to intelligence agencies, but also ushered in an era in which leaders use terrorism to garner support for their policies by exploiting the fear of their citizens. This is the era in which we still operate today.

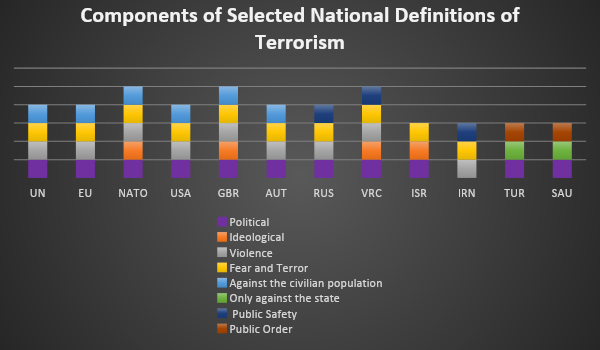

Before looking at the definitions of terrorism adopted in legal texts after 2001, which overall have increasingly become tailored to suit specific domestic circumstances as well as different types of criminal, but not terror-related activities, it is useful to see how academia can shed light on this issue. Typically, there is consensus that terrorism involves the deliberate use of shocking violence against non-combatants, chosen at random, with the aim of creating political pressure, as Michael Walzer and other scholars have contended. Still, no single definition prevails. Similarly, in the transatlantic realm, where greater policy coherence may be expected, no universal definition exists. However, the legal texts of the EU, Austria and the United States on terrorism consist of essentially the same components, defining it as a violent criminal act intended to intimidate or coerce the civilian population, influence the policy of a state or organisation, or destabilise or destroy the political, constitutional, economic or social structures of a country or international organisation.

However, states have increasingly adopted more specific definitions of terrorism, taking into consideration particular political circumstances. Chinese law defines terrorism as “propositions and actions that create social panic (…) through methods such as violence, destruction, intimidation, so as to achieve their political, ideological or other objectives.” Unlike the EU’s definition, China’s includes the word “proposition,” which could mean anything from a verbal statement to a protest sign. This clearly broadens the possible interpretations of terrorism, and given China’s unique definition, it is conceivable how the government could describe protestors in Hong Kong as “showing signs of terrorism” in August 2019.

Saudi Arabia’s approach to defining terrorism also demonstrates direct links to the country’s specific domestic security challenges. A Saudi law of 2013 defines terrorism as:

[a]ny act undertaken by the offender directly or indirectly in pursuance of an individual or collective criminal enterprise intended to disturb the public order, destabilize the security of society or the stability of the state, expose its national unity to danger, obstruct the implementation of the organic law or some of its provisions, harm the reputation of the state or its standing, endanger any of the state facilities or its natural resources, force any of its authorities to do or abstain from doing something, or threaten to carry out actions leading to any of the aforementioned objectives or encourage their accomplishment.

First, the Saudi government includes “natural resources,” which is unique to the Saudi definition and underscores the potential influence of domestic circumstances on the interpretation of crimes. Since nearly a quarter of Saudi Arabia’s GDP comes from the exploitation of natural resources, this inclusion could be seen as the equivalent of the term “economic” in the EU’s definition. Second, and more problematic, is the use of ambiguous terms such as “public order” and “reputation of the state,” which open the definition to numerous interpretations, including peaceful forms of political protests, considering that the use of violence is not a necessary precondition.

The definition used by the Islamic Republic of Iran is the only one to include a religious component. According to Iranian law “Any person who resorts to weapons to cause terror and fear or to breach public security and freedom shall be considered as a mohareb and corrupt on earth.” The term mohareb, literally meaning “waging war against God,” is used in Iranian jurisprudence to classify crimes against the state. Thus, anyone who uses violence against the Iranian state commits a crime against God, justifying capital punishment. As U.S. Armed Forces, having killed an Iranian general, threaten Iranian security and freedom, the government classified them as terrorists and thus enemies of God, rhetoric which can easily translate into very dangerous actions.

The following graph lists the different components of twelve definitions of terrorism, highlighting the various emphases which states have chosen. The lack of uniformity makes evident the increased politicisation of the term. This trend is concerning, as the more a state relies on specific domestic factors to define terrorism, the more potential there is for overreaction, manipulation and abuse. Consequently, both politicians and citizens should be attentive to the possible misuse of the term, for this is the real danger terrorism poses; it creates fear which leads people to willingly give up their rights and liberties in the hope of gaining security.