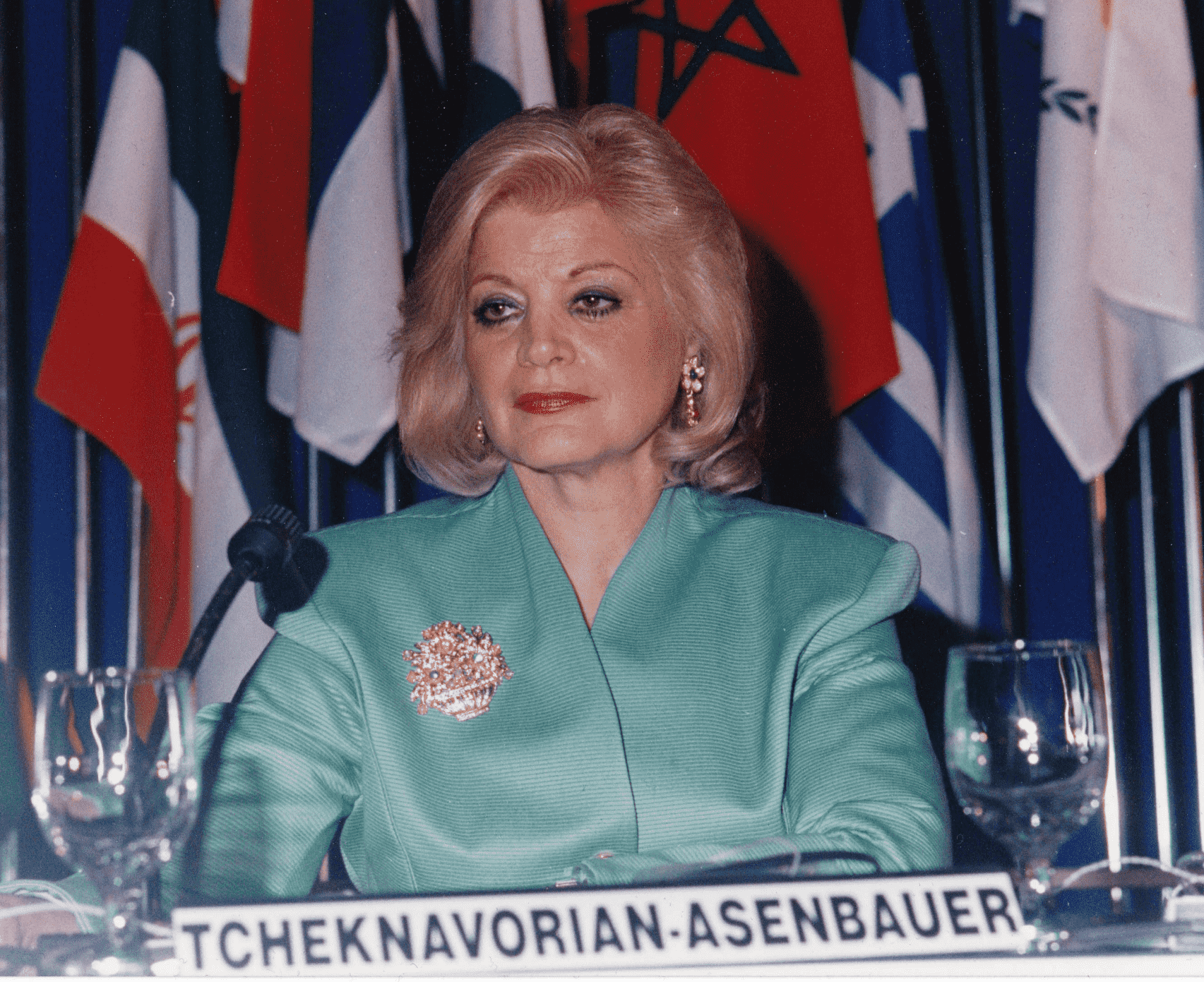

Despite the widespread consensus on the need to combat climate change, the global community continues to disagree on the exact measures needed to accomplish this objective. This dissension was most recently seen at the annual Conference of the Parties (COP), when representatives struggled to come to an agreement on how to phase out fossil fuels. To date, the only universally ratified environmental treaty remains the Montreal Protocol, a multilateral agreement on the phasing out of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) – a chemical compound that was widely used in the refrigeration industry and is known to have heavily contributed to the formation of a hole in the ozone layer. Thanks to the joint effort of policymakers, industry and scientists, the ozone layer is on track to recover completely within the next 40 years. As one of the four implementing agencies of the Multilateral Fund, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), with its headquarters in Vienna, played a decisive role in accelerating the implementation of the Montreal Protocol, largely thanks to one brave woman: Dr. Archalus Tcheknavorian-Asenbauer. Through her perseverance and consistency in questioning the status quo, she paved a more efficient and cost-effective way of solving technological issues for the benefit of humanity. Diplomatic Academy alumna Milica Vujačić sat down with Dr. Archalus Tcheknavorian-Asenbauer, former Managing Director at UNIDO and chemical engineer, to talk to her about how UNIDO shaped the Montreal Protocol.

MV: Dr. Tcheknavorian-Asenbauer, you have had a very successful career at UNIDO which started in 1970 and lasted until 1995. Can you give us a short overview of your career at the Organization?

ATA: I started working at UNIDO in September of 1970 as a young professional, P1, and worked myself up to Managing Director, D2, over the course of the next 26 years until my retirement. During my time at UNIDO, I traveled to 175 countries in total.

MV: Why did you join UNIDO?

ATA: My goal has always been to help developing countries. During my time at UNIDO, I was very active in Africa, Latin America and Asia. I developed a large number of programmes and actively contributed to many fields, with the Montreal Protocol being my last big programme. What is important to understand – and this applies to environment and climate change projects in general – is that nations need their own industry and agriculture to generate income, so that people have a place to work. Otherwise we will never be able to eradicate poverty. In the quest for a more sustainable planet, the development of nations must never be forgotten. Every human being has the right to a basic quality of life. Throughout my career, including within the Montreal Protocol, I continuously insisted on the inclusion and consideration of least developed and developing countries.

MV: During your time at UNIDO, you were instrumental in the introduction of an environmental programme in the Organization. This was during a time when environmental impact was not yet widely discussed. What pushed you to advocate for environmental protection and sound chemicals management?

ATA: Environmental protection only became a topic of discussion in the early 1980s. Around that time, I learned that it was common practice for the waste water of slaughterhouses in Europe to be directly discharged into rivers. That became the first environmental programme that I was involved in. Shortly after, a project for reducing chemical use in the textiles industry followed. I started to do a lot for the environment and came to be known as an environmentalist in my Organization.

MV: Originally, UNIDO was not involved in the Montreal Protocol. Today, UNIDO is one of its four implementing agencies. What brought about the involvement of an industrial organization in this environmental treaty?

ATA: The first meeting of the Montreal Protocol took place in Vienna in 1990. UNIDO was not invited and was not aware that the meeting was taking place. Shortly after, I flew to Montreal on a different occasion. During my meeting with the Canadian minister of industry, I found out that the last meeting of the conference for the Montreal Protocol in the newly opened office was taking place as we were speaking. The meeting was due to end in a couple of hours, so I asked the minister whether it would be possible for me to attend.

Though he was hesitant at first, I persisted and was taken to the conference. After having listened to the presentations, I raised my hand and said “Ladies and gentlemen, I carefully listened to the presentations and discussions and I was very surprised to hear that you are discussing technology transfer in industry while the UN organization that is responsible for this, namely UNIDO, is not a member of this programme.” After a moment of silence, people started to applaud. This was the beginning of UNIDO’s involvement in the Protocol.

Back in Vienna, I briefed the Director General (DG), who himself traveled to Montreal a little while later to have a follow-up meeting with the Chief Officer for the Multilateral Fund for the Implementation of the Montreal Protocol. During this meeting, the DG asked the Chief Officer why UNIDO had not been invited as a member to the Montreal Protocol, to which he received the answer that the total budget of the programme had already been completely divided up between the World Bank, UNDP and UNEP. The DG then negotiated observer status for UNIDO. After having participated twice in the meetings, I spoke to representatives of the World Bank and UNDP during a conference which took place in Thailand. I negotiated that the World Bank and UNDP give UNIDO 15% and 10% of their budget shares, respectively. In the end, UNIDO secured 25% of the total budget. Starting 1993, we had a budget for the Montreal Protocol and thereby automatically became a member.

MV: What was your role in the Montreal Protocol?

ATA: In 1994, I went to another conference in Thailand. There, the World Bank was presenting their proposal for transitioning away from CFCs: each project was to take 4 to 5 years with expected costs of 25 to 30 million dollars. I requested the floor, saying that as an engineer, I could not accept this proposal and insisting the time frame be decreased to 6 months maximum. The representative from the World Bank then announced that I was to prove at the next meeting in Montreal that this was possible.

When I returned to Vienna, I explained to the DG that I needed to go to my hometown Tehran. In Tehran, I met with the responsible minister and asked him for permission to access Iran’s refrigeration industry. After analysing the industry, I designed and implemented a plan that would introduce a new technology to eliminate the use of CFCs. For 6 months, I travelled back and forth between Vienna and Tehran and changed the production to a CFC-free refrigeration industry during this time. In February 1995, I presented my results at the Montreal Protocol Conference. To everybody’s astonishment, I proved that it was possible to change technologies in a much shorter time frame than originally proposed. As a result, the timeframe for projects was reduced to 6 to 12 months. In addition, the planned number of projects per year was increased from 40 to 100. The estimated average cost sank from 25 million dollars to 4 to 5 million dollars. In a short period of time, the Montreal Protocol became a success story. Ultimately, I received an award in 2000 by the United States as a recognition for my contribution to the Montreal Protocol.

MV: Dr. Tcheknavorian-Asenbauer, do you have any advice for the next generation of diplomats?

ATA: Through my experience of traveling all around the world and implementing my projects, I learned that one of the most important skills to have is being able to listen to one’s counterparts. Government representatives always asked specifically to talk to me, because they knew I would truly listen to what they had to say. Instead of trying to impose our own solutions on them during my visits, I always made an effort to work together with them. For instance, in the early 1980s a conference on banning the use of chemicals in pesticides took place in Stockholm. As a result of the ban, the British company Imperial Chemical Industries started to produce non-chemical pesticides.

Shortly after, China requested my mission. Upon my arrival in China, I was informed that the Chinese wanted to develop their own technology for bio-pesticides. Due to patent law, the existing technology could not be accessed for 13 years, making a technology transfer impossible. I flew to India, to one of the biotechnology centres that I had previously developed there, to find suitable experts. After a week of interviews, I found two people that flew back to Beijing with me. Together with Chinese experts, they developed the needed technology in less than one and a half years. This was crucial for China, because it desperately needed pesticides to be able to feed its large population. Because we listened to their needs and worked together with them, they were quickly able to switch to chemical-free pesticides.

Dr. Archalus Tcheknavorian-Asenbauer, former Managing Director for Industrial Sectors and the Environment at the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) in Vienna, is an Iranian-Armenian chemical engineer. She received her PhD at the Technical University of Vienna in Industrial Operations and Catalytic Chemical Processes. Following her retirement, Dr. Tcheknavorian-Asenbauer assumed numerous advisory positions for various UN agencies and international organizations.

Written by Milica Vujačić; Edited by Jason Kancylarz

Photo credit to: Daniel Olah, unsplash and Milica Vujačić