This year, Austria commemorates the 100th anniversary of the deaths of four titans of Viennese modernism: Gustav Klimt, Egon Schiele, Kolomon Moser and Otto Wager. Yet 2018 also marks several other notable anniversaries which shaped the politics and identity of a nation.

1918 was a fateful year for the Austrian monarchy. World War I had crushed kings and toppled empires, casting a long shadow over the next century. Its legacy affected the fate of people and nations, and ushered in the birth of a turbulent republic.

Following the horrors of Europe’s first total war, the state with eleven nationalities became impossible to govern and Austria-Hungary dissolved within a few weeks. New successor states emerged and nationalism was on the rise.

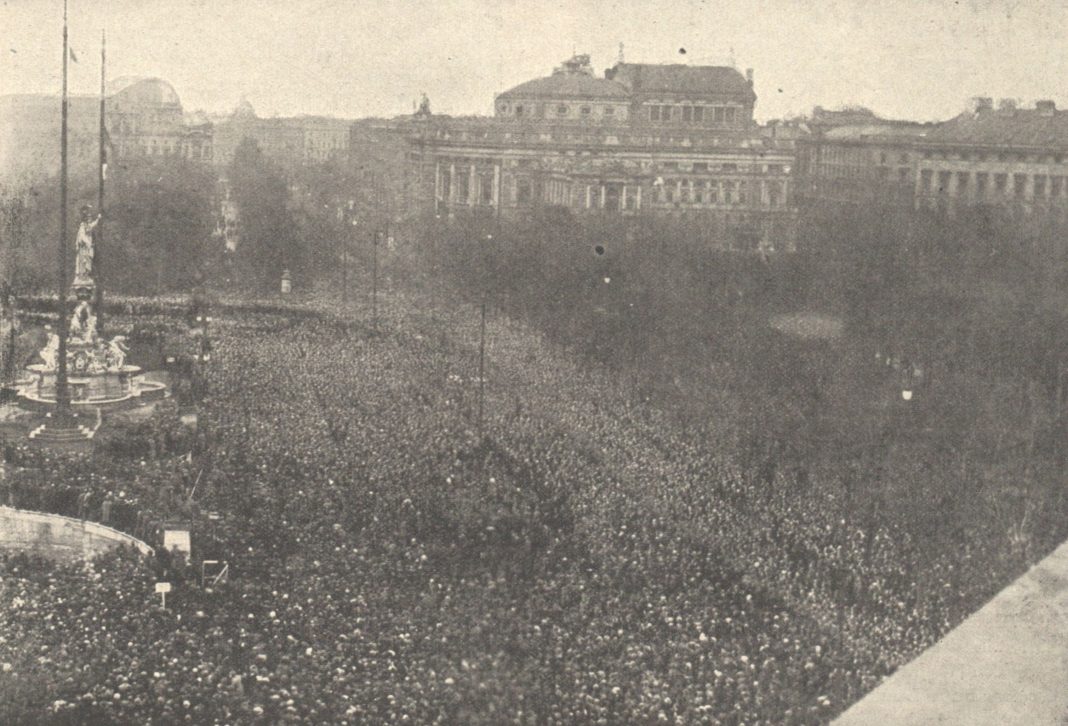

In November, Emperor Charles I, abdicated the throne and went into exile in Switzerland, ending the reign of the Habsburg family after almost 640 years. The following day the National Assembly proclaimed a German-Austrian republic. However the Allied Powers had failed to take the considerations of the young Austrian state into account. They forbade the much-desired unification with Germany, and the Paris peace treaties worsened the situation, eventually plunging Europe into a second war twenty years after their signing. It was only after World War II that Europe was able to reach an agreement and the possibility of permanent peace.

During these uncertain years, Austrians struggled to form a genuine identity. The young state attempted to rid itself of the monarchy and form solidarity among its citizens. Ironically, a century later, modern Austrian identity is mainly built on the memories of the Habsburg era: Austrians take great pride in Sissi, Viennese Balls and Schönbrunn Palace; and it is this imperial flair that attracts tourists from all over the world today. However, the beauty and grandeur masks a painful part of history which plagues contemporary Austria to this day. The year 2018 is not just the anniversary of the Republic, but its annexation to the Third Reich.

In January, Chancellor Sebastian Kurz appealed to the Austrians to never forget the “the sad and shameful days of March 1938.” Kurz’s statements came against the backdrop of anti-Semitic allegations against a student fraternity, which has been accused of publishing Holocaust-glorifying songs. The fraternity’s members include a candidate from the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ), who is running for election in Lower Austria. The international media exploited the scandal turning an intense spotlight on Austria.

“We bear a clear historic responsibility that the new government clearly recognises,” Kurz said in the midst of the media hailstorm. However whether there is truth in that statement remains to be seen. The last few years have witnessed a refugee crisis and inflammatory statements from current leadership about the islamization of Europe.

According to Federal President Alexander Van der Bellen, the commemorative year is the perfect occasion to sensitise the public to present-day challenges, among them Austria’s upcoming presidency in the EU Council. “In 2018 Austria should seriously cope with its eventful history and draw lessons from the past,” he said.

Van der Bellen reminded the Austrian of their responsibility in the refugee crisis. As Austria sees itself as dedicated to human rights, the government included another anniversary – the 1948 adoption of the Human Rights Declaration – in the commemorative celebrations.

The key component of the commemorative year is the Austrian Museum of Contemporary History, which serves as a symbol for the complexities of modern Austrian identity. Long discussions were held over the naming. How much of the Hapsburg era should it include and where does Austrian history actually begin? Little has been said about the exhibits themselves, as the physical representations of Austrian history can often be as chaotic as the actual events. The resignation document of the last Habsburg Emperor Charles burned in 1927 and the Declaration of Independence of 1945 was lost and likely destroyed.

This is not the first time Austria planned to open a history museum. Several other attempts date back as late as the 1940’s; however, disputes between political parties as well as budgetary questions slowed the process down. Other regional governments worked on their own projects, like the Government of Lower Austria which opened up its own museum of Austrian history last year. Now, Austria will have two history museums after decades of disagreement.

The dispute reflects Austria’s struggle over history and identity between the different political and social groups.

The commemorative year is aimed to solemnly unite the Austrian society, which was involuntarily created hundred years ago. Whether it can truly do so, remains to be seen.